Reviving Reefs

On Koh Samui, local artisan Yupaporn Wanitcharoen has transformed her love of textiles into a mission to heal the sea-joining hands with neighbours, divers, and visitors to restore coral reefs and revive the island’s fragile marine life.

Words: Bella Luna

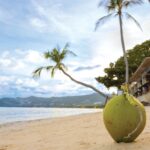

To the eyes of a visitor, Koh Samui is a postcard of paradise. Its beaches shimmer with white sand, coconut palms lean lazily over azure waters, and coral reefs stretch like underwater rainforests just beneath the waves. But if we pause, if we look more closely, we begin to see the fragile balance that keeps this island alive. And we also see the threats that could unravel it.

Like so many islands around the world, Samui faces an overwhelming problem with waste, especially plastic. Plastic bottles and food containers wash ashore with every tide. Discarded nets lie tangled in the shallows, and single-use cups pile up behind markets and along roadsides. Waste management here is a daunting task: the island’s infrastructure was never designed for the millions of visitors who now arrive each year.

The cost of this carelessness is most visible beneath the surface. Coral reefs, which take centuries to grow, are being shattered in seconds. Tourists stepping into shallow lagoons, fishermen dragging nets across seagrass beds, and plastics drifting in the current all leave their scars. Coral, though resilient, is not indestructible. Break it, and entire ecosystems unravel. Fish lose their breeding grounds. Turtles lose their feeding beds. The very reefs that protect Samui’s coastlines from storms begin to vanish.

And yet, there is hope. Hope born not of grand policies, but of local people—ordinary citizens with extraordinary determination. One of them is Yupaporn Wanitcharoen.

Her story begins not with coral, but with cloth. When the world came to a standstill during the COVID-19 pandemic, Yupaporn’s hotel stood empty. Many might have despaired. She chose instead to search for meaning. After meditating on how best to serve her community, she remembered her love of textiles. She began learning the art of natural dyeing, using salt to draw pigments from leaves and flowers.

By chance, while being interviewed and photographed about her work on textiles by the sea, she discovered that seawater made the colours bloom more vividly. Each time she returned to soak her fabrics, she also noticed something else: the sheer volume of waste littering the shoreline. Plastic bottles, wrappers, fishing debris. Beauty and devastation, side by side.

That was her turning point.

She began working with other Samui residents tackling the waste problem

in creative ways—some turning derelict trawlers into eco-friendly building bricks, others experimenting with solar-powered homes. But her heart was pulled most strongly toward the sea, and the corals silently suffering beneath the surface.

With guidance from Vinythai Company, together with the Coral Conservation Foundation who has over two decades of experience in coral restoration, Yupaporn joined a coral rehabilitation project on Laem Son beach. This stretch of coast is rich in seagrass and marine turtles, yet it is unprotected. Fishermen and local workers often wade into the shallows to gather shrimp, crabs, and bivalves. Without realising it, their footsteps crush fragile coral colonies, and their nets tear apart the very structures that sustain marine life.

The work of rehabilitation is delicate, patient, and profoundly hopeful. Broken fragments of coral are collected and secured in PVC pipes, where they are nurtured until they grow strong enough to return to the reef. Over time, these fragments transform into thriving “fish apartments,” offering shelter and food for marine life.

“It’s important to show people that coral can come back,” Yupaporn says. “When they see fish return, they understand why protecting it matters.”

And it is not just locals who can help. Visitors—those who travel across the world to experience Samui’s beauty—can play a direct role in its protection. Tourists are invited to join coral rehabilitation trips: collecting broken coral, releasing young colonies into four-to-seven-metre-deep waters, and witnessing firsthand the resilience of nature.

This is conservation at its most tangible. It is not about watching from afar, but >> about immersing yourself in the story of the island. Imagine returning home from Samui not only with photographs of perfect beaches, but with the knowledge that you have helped rebuild a living reef.

The challenge of waste remains vast. Yupaporn dreams of a future where children on Samui are taught not to litter, where every household embraces reusable bottles and cups, and where the sight of a plastic bag drifting across the tide becomes a memory, not a reality.

But change begins with awareness, and awareness grows when people see what is at stake. When you stand on Laem Son’s sands and gaze at the sea, you are looking at a world as intricate and fragile as any rainforest or savannah Sir David Attenborough has ever described. A world worth fighting for.

The story of Samui is not one of despair, but of resilience. The island may be struggling under the weight of waste, but people like Yupaporn are proving that one person’s resolve can ripple outwards, transforming communities and ecosystems alike.

As travellers, we too have a role. When you order a drink, choose a reusable cup. When you shop, say no to plastic bags. And if you truly want to leave a mark, join a coral rehabilitation programme. Step onto a boat, dive into the water, and place a fragment of coral back where it belongs. In doing so, you become part of the story of renewal.

Samui remains a paradise but it is a paradise that needs guardians. And together—with the passion of its people and the care of its visitors—it can remain a sanctuary not just for us, but for the countless forms of life that call it home.