Basket Case

In Samui, tourist sip coconuts by the sea. One woman looked at discarded banana trees and saw something else entirely: strength, endurance, and a business worth fighting for.

Words & Photography: Mimi Grachangnetara / Pangchanak Pangviphas

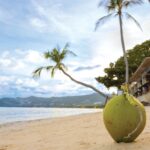

On Koh Samui, paradsie sells itself. White sand, sway-ing palms, coconut cocktails, infinity pools. The kind of place where tourists come to forget that the real world exists. But scratch at the surface and you’ll find another story-one that doesn’t come with a glossy brochure or a welcome drink.

Naovarat “Nadee” Wannaprasert is not from Samui. She came from the Central province of Angthong, a couple of hours away, on what was supposed to be just a holiday during the strange, hollow days of COVID.

With no relatives here and no backup plan, she rented a motorbike and rode around aimlessly, taking in the island. What she found wasn’t the postcard version. It was banana trees—cut, abandoned, left to rot on the side of the road like yesterday’s trash.

“I saw piles of stems everywhere,” she recalls. “People planted bananas only to shade their durian trees. Once the durians grew strong enough, the bananas were cut and dis- carded. It didn’t sit right with me.”

That chance observation was the beginning of a five-year odyssey—one that would turn her from visitor to community builder, and place Samui on the map for a rare kind of eco- entrepreneurship: banana-rope craft.

Back in Ang Thong, Nadee was no stranger to handicraft. Her work there had earned the coveted 4-star OTOP (One Tambon One Product) certification. So when she returned to Samui, she carried, together with her curiosity, the skills and vision to give waste a second life.

The path wasn’t easy. “The first time I proposed banana-fibre weaving to local officials, they thought I was, literally, bananas,” she laughs. “Nobody knew me here. They wondered who this woman was, telling them about banana stems.”

But Nadee is nothing if not persistent. She relocated to Samui in 2021, rented a home and a shopfront, and began lobbying for support. With help from Ang Thong labour of- ficials, she finally convinced Surat Thani authorities to fund community training. Soon, villagers who had once dis- missed the “mad” idea were learning to weave banana rope into everyday essentials.

The transition wasn’t without cultural hurdles. In Thailand, the Tani banana (Musa balbisiana)—whose fibres are known for strength—is shrouded in folklore. Some locals avoid planting it, believing it is inhabited by a female spirit named “Naang Tani”.

“In Ang Thong, Tani bananas are respected for their endurance,” says Nadee. “We use them for basketry. But on Samui, people hesitated because of old beliefs. It took time to show them the benefits.”

Once the locals saw how the leaves resisted tearing and how the fibres outlasted other natural materials, the mindset shifted. The discarded tree became a resource, even a treasure.

Step into Nadee’s workshop today, and you’ll see how far one tree can go. Soap, pa- per, bags, even experimental cookies made from banana stem fibres—the possibilities seem endless. The fibres, she explains, are second only to silk in strength. “One banana tree can become so many things,” she says, her eyes lighting up.

Among her proudest creations is a woven bag designed to carry kalamair, a sticky local sweet. The design nods to tradition while proving the versatility of banana rope in modern life.

Her commitment to zero-waste is uncompromising. Every part of the tree is used, and her products—unlike bamboo, water hyacinth, or krajood (bulrush)—don’t develop mold. With care, they last a decade or more.

The turning point came, thanks to another woman entrepreneur who invited Nadee to showcase her products at a local market. The response was overwhelming. Soon after, a major department store placed bulk orders.

“Hotels liked the products but hesitated at first,” Nadee recalls. “I promised them: no matter how big the order, I will deliver on time. During COVID, we had a two-month deadline. I finished in 45 days. That built trust.”

Word of mouth carried her work further than any online shop could. Tourists stumbled upon her workshop, then told others. International journalists joined her hands-on workshops and left amazed that a banana tree could transform into soap, bags, or textiles.

Nadee doesn’t see her venture as hers alone. The women and men she trained on Samui continue to weave banana-rope products, generating income and reviving respect for local craft traditions.

“When I came here, people thought I was a scammer,” she admits. “But I stayed, worked hard, and shared my skills. I showed them this wasn’t about me—it was about giving value to what we already have.”

Her daughter, a chef, has since joined her on Samui, adding another layer of hospitality to the workshops. Guests now enjoy snacks and coffee while learning to weave, turning each session into a memory stitched with taste and craft.

For Nadee, the banana tree is nothing short of being a metaphor for resilience. From rejection to recognition, her journey reflects the same endurance as the fibres she weaves.

“There were times I was in debt, times my relatives told me to stop,” she says. “But I believed in the work. Nobody else was doing it. I wanted locals to believe in their own skills, to see their value.”

Today, her products are certified OTOP Premium and cherished by travellers seeking souvenirs with soul. But perhaps her greatest achievement lies in the invisible threads—linking Ang Thong to Samui, tradition to innovation, and waste to worth.

“Everyone has problems,” she says with a smile. “But if you carry positive energy inside and believe in yourself, anything is possible.”

On Samui, thanks to one determined woman and a discarded tree, that belief is now woven into baskets, bags, and beyond.